Interview with Author Gregory Maguire

This post may contain affiliate links.

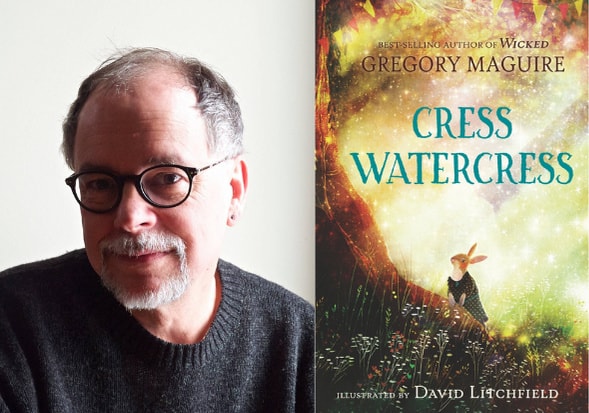

Gregory Maguire is the author of Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, which inspired the Wicked musical. He is also the author of several books for children, including the forthcoming Cress Watercress as well as What-the-Dickens, a New York Times bestseller and Egg & Spoon, a New York Times Book Review Notable Children’s Book of the Year.

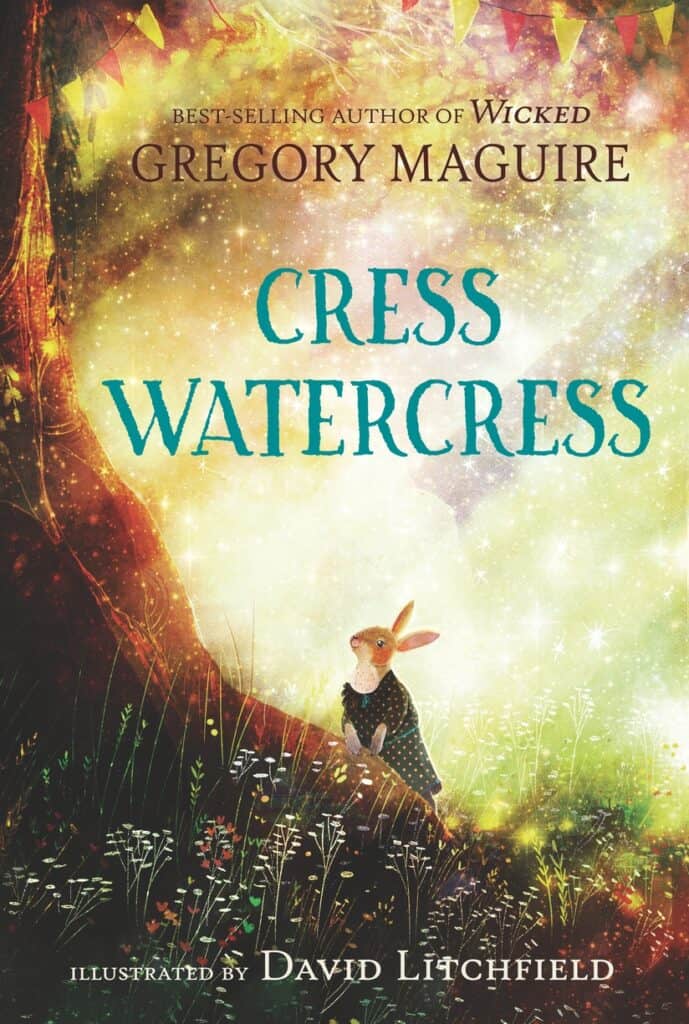

His next book, Cress Watercress, arrives in bookstores on 3/29/22. It’s a stunningly beautiful story about a fatherless rabbit named Cress who is on a journey to understand her inner world, reflected by her outer world and its stories, with delicious figurative language and precise word choice with characters who are immensely lovable. (It’s my favorite book of the year!)

I am thrilled to share a recent interview with Gregory Maguire about his new book, writing process, and favorite children’s books.

Interview with Author Gregory Maguire

Melissa: I love your use of language and imagery in Cress Watercress. (“The setting sun was a lumpy clementine…“) Can you tell me about your process? Do you walk through the world differently than non-writers?

Gregory: This is the kind of wonderful question that creative people ask themselves and can’t know the answer to. (Is the blue you see in the sky the same blue I see? Experiential miasmas…) I once asked Maurice Sendak what he pictured when he read THE ILIAD, but I had subtly asked the wrong question, and never rephrased it, and then he died, so I don’t know the answer. What I was TRYING to get at was did he picture what he was reading as non-artists might (this, then that), or as a film-maker might, in black and white or Technicolor, or—and this is what I was really curious about—did he picture great stories in terms of Maurice Sendak drawings? Was his imagination a free-floating endless scroll of unpublished Sendakiana? I wish I knew. I suspect it wasn’t, that Sendak drawings came out of his pen and brush after being fed through his hand onto the paper—but I’ll never know.

But to answer your question. I suppose I am a curious blend of revolting earnestness and absurdism. My father was something of a humorous writer and a well-known raconteur and journalist around town (Albany NY) and the Irish side of that largely Irish city was replete with good storytellers. Certain inanities appealed to me from childhood—“Rocky and Bullwinkle” (esp. the Fractured Fairy Tales!); Alice in Wonderland. The hums of Pooh. As I got older, skits from the Carol Burnett show.

The earnestness is a dreadful liability. I think about serious things all the time. I think that I cast off nonsequiturs and try to use language as a way to surprise and delight is, in some ways, a deflection from a slightly morbid tendency that all Irish Catholics come by honorably and that my own family situation institutionalized deep down. (I spent part of my infancy in an orphanage.)

But the truth about looking through the world for what it shows you is that you have to interpret what you see, and I find that the ability to play with language—to twist and tweak it just a hair’s-breadth—it’s like making something funny. You arrest the attention of the reader just this side of drawing attention to yourself as a writer. (That is a tricky metric to honor and I’m sure I fall over the edge all the time.) “A lumpy clementine.” I don’t want readers to think, “Oh, what a clever writer!” I want them to think, “Oh, yes, I’ve seen that sun! But never thought of it like that, and next time, I might. Now to go on.”

Final about process. Since I taught myself to write stories between first and fourth grades, my method has not evolved a scrap. I start with the first sentence and keep going until I reach the last one. I admire and envy people who write in bursts of inspiration and sort out the order later. I’m much more plodding. Though I do hold off beginning until I’m ready. (I realized after the fact I could have started: “In a hole in the ground there lived a rabbit.” But there she would be, stuck in that hole. I had to wait to see something happening. “Is everyone ready?” are Mama’s words at the end of the first paragraph. She’s talking to me, too. I nod, and push on to the next paragraph.

Melissa: With growing (kid) writers, what is the top piece of advice you give them — either with your children or students at schools you visit?

Gregory: The TOP advice? Well, it would have to be Ben Shahn’s in The Shape of Content: Close nothing off. Read everything. Though you can’t say that to kids. So just READ READ READ.

And don’t let the bloodsucking maw of the internet sink its incisors too deeply in your skin. Well, that’s a lost battle, and for me too. Never mind.

Here are very brief pieces of advice I give to fledgling writers of every age:

1) read

2) write every day—if not fiction, then in a journal, or in a letter (or a post I suppose). It doesn’t have to be much—a few lines. But something. Writing is like exercise, and you have to do it every day to keep in shape.

3) if you get blocked, put the work on the side of your desk.

4) note I didn’t say “put it in a drawer.” DON’T put it in a drawer. Leave it out where it can stare at your reproachfully, balefully, until you come back to it.

5) if you’re blocked, go for a walk. You don’t need to think about your project, but you will be working things out subconsciously.

6) if you’re DEEPLY blocked, pose a question to your dream mind on a piece of paper and leave it by the side of your bed when you turn off your lamp. Something like “Why did Squinchy happen to have a set of jumper cables in her Sunday go-to-meeting purse?” Whatever it is you need to know. When you wake up, there is a very good chance that the elves of your subconscious, like the minions in a deposit library, will have been mining for ideas all night and will have delivered something to your inbox in the morning. I’m not kidding about this. I rely deeply on my subconscious to keep the circuits sizzling while I am asleep. They’re the night shift and they do the important work.

Melissa: Some of my readers are aspiring children’s book writers. Can you share a bit about how you find your story ideas with them?

Gregory: I wish I could remember who first told the old joke, “I tell people who ask me where I get my ideas: at Woolworth’s.”

But there’s truth to this as to any joke.

An idea is, I think, a manifestation, or you might say a mestastasization (auto-correct don’t like that word), of some perceived reality, be it a reality about an appetite you have or perceive others have, or an image, or a setup, or a specific character, as wrought through the discriminating fine-mesh sieve of your imagination. The novelist Jane Langton once put it in a six-word proposal: “What if? Then what? So what?” She was talking about fantasy for children—what if a baby elephant saw his mother shot by a hunter and ran away to Paris, etc.—but it’s a similar stratagem for any kind of story-telling.

One can back into a story in any number of ways. The idea of Cress as a fatherless rabbit came second. The earlier impulse was thinking about one of my kids, and how I wasn’t sure that the notion that strong emotions aren’t merely instances to survive and to grow from, but are cyclical, and the important lesson I didn’t think this child had yet taken on is that they will return. Bibliotherapy only gets you to the last page in a book, but in real life, flashes of old anger, love, regret, fear, wash over us constantly. The older we get, the more we know we are going to survive their return, and get beyond them, too. The young don’t yet have the time to know that. That was the start of CRESS, and I worked backward to find a character who would be properly situated to have to deal with these matters.

Melissa: Do you have a favorite character in this story, and why?

Gregory: Hmmm. I love Cress herself because she is so emotionally volatile. I was like that as a kid (“sensatif!”). I liked writing nearly all the characters, though. Lady Agnes Cabbage appears in nearly all my books in one way or another. The chinchilla was a happy surprise. When she mentioned she had a chinchilla I didn’t know it was going to speak until the next line.

I have a secret affection for Tunk the Honeybear, too, because he means well but is too lumbering to do anything delicately. I know people like that. I am people like that.

Melissa: What were your favorite children’s books that you read to your children when they were younger? Or, what are your five favorite children’s books?

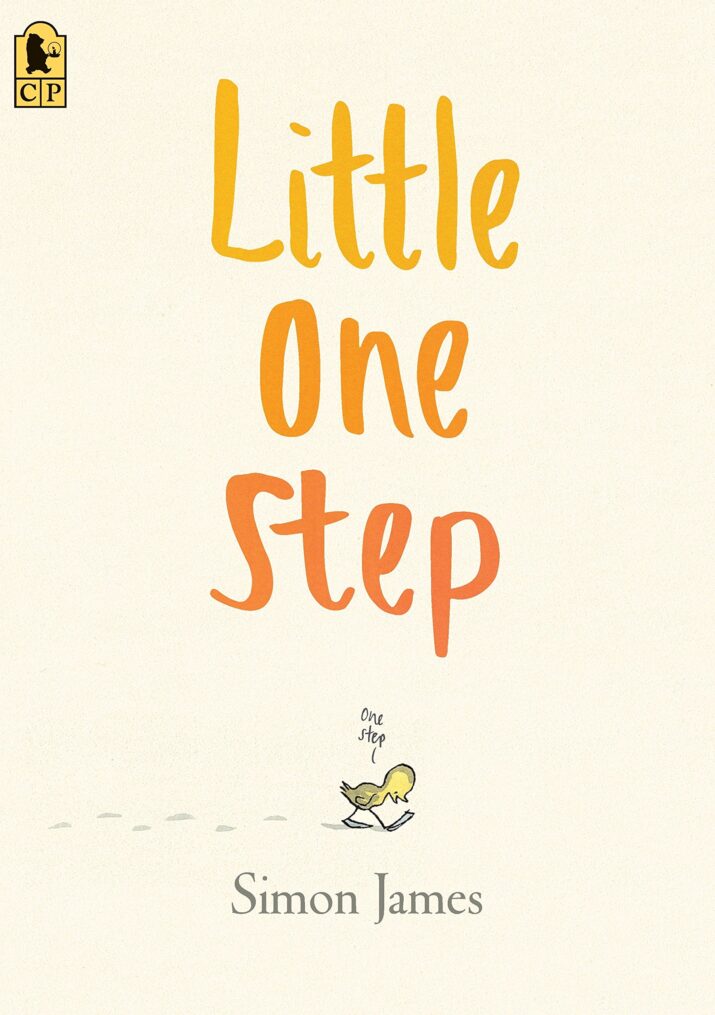

Gregory: Aha! Now we had some REAL favorites in childhood that belong to our household and don’t necessarily mean too much to others. But who knows? They include the Gaspard and Lisa books, which are originally in French I think; Father Fox’s Pennyrhymes. The two Rosemary Wells books of Mother Goose rhymes. (I didn’t think I was going to like them but they’re absolutely classic totems in this household.) A very simple story about a new duckling called Little One-Step. Several Sendak books.

Gregory: Aha! Now we had some REAL favorites in childhood that belong to our household and don’t necessarily mean too much to others. But who knows? They include the Gaspard and Lisa books, which are originally in French I think; Father Fox’s Pennyrhymes. The two Rosemary Wells books of Mother Goose rhymes. (I didn’t think I was going to like them but they’re absolutely classic totems in this household.) A very simple story about a new duckling called Little One-Step. Several Sendak books.

My favorites in childhood? I won’t talk about picture books because I remember those more from reading them to my baby siblings. The Golden Age of childhood reading for me—fourth through eighth grade—brought me to C S Lewis’s Narnia, to Harriet the Spy, to The Diamond in the Window by Jane Langton, to A Wrinkle in Time, Pretty standard fare for someone who would grow up to write fantasy (Harriet being the exception, though she taught me how to be honest and to keep a journal, and everything else descends from that). And for a fifth, since you asked for five, I’ll mention a transitional book for me, read in high school: The Once and Future King. Transitional in that the first volume, The Sword in the Stone, was published for children (as I understand it, though maybe not—I’ve never had full clarity on that). But it was a bildungsroman of the young King Arthur, so about a child). That wonderful, funny, dear, complicated novel gave me both the template and the courage to consider writing Wicked some 25 years later. A very important book in my life.

About Gregory Maguire

GREGORY MAGUIRE is the author of the incredibly popular books in the Wicked Years series, including Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, which inspired the musical. He is also the author of several books for children, including What-the-Dickens, a New York Times bestseller, and Egg & Spoon, a New York Times Book Review Notable Children’s Book of the Year. Gregory Maguire lives outside Boston.

About Cress Watercress

Penguin Random House Amazon Bookshop

Penguin Random House Amazon Bookshop

From the publisher:

Some of David Litchfield’s artwork for Cress Watercress seems to me like Aesop’s fables done in stained glass. Other pieces are scattershot windmill art, breezy and incidental as a summer’s day. Homespun, handsome, and as full of feeling as any child. In fact, it is the child’s life of feelings that I was eager to capture in Cress Watercress. When young, we are lovingly shown by our parents and teachers that feelings are real and that they are valid, but we’re given little guidance as to their schedule or life cycle. We’re expected to learn of the timetable of moods all on our own. If we’re traumatized—and who isn’t?—we can be strengthened when we understand that dark moods may often return, but they will lift again. Cress Watercress, through its lighthearted adventures, portrays this dawning realization in a young creature.

KEEP READING

That was a super interview. Thanks, very much! Lots to think about after reading it. And best of luck to Gregory Maguire on the release of Cress Watercress.

I read an ARC and very much enjoyed the lush writing in this novel. I was pleasantly delighted by the feel of a storyteller as I read.