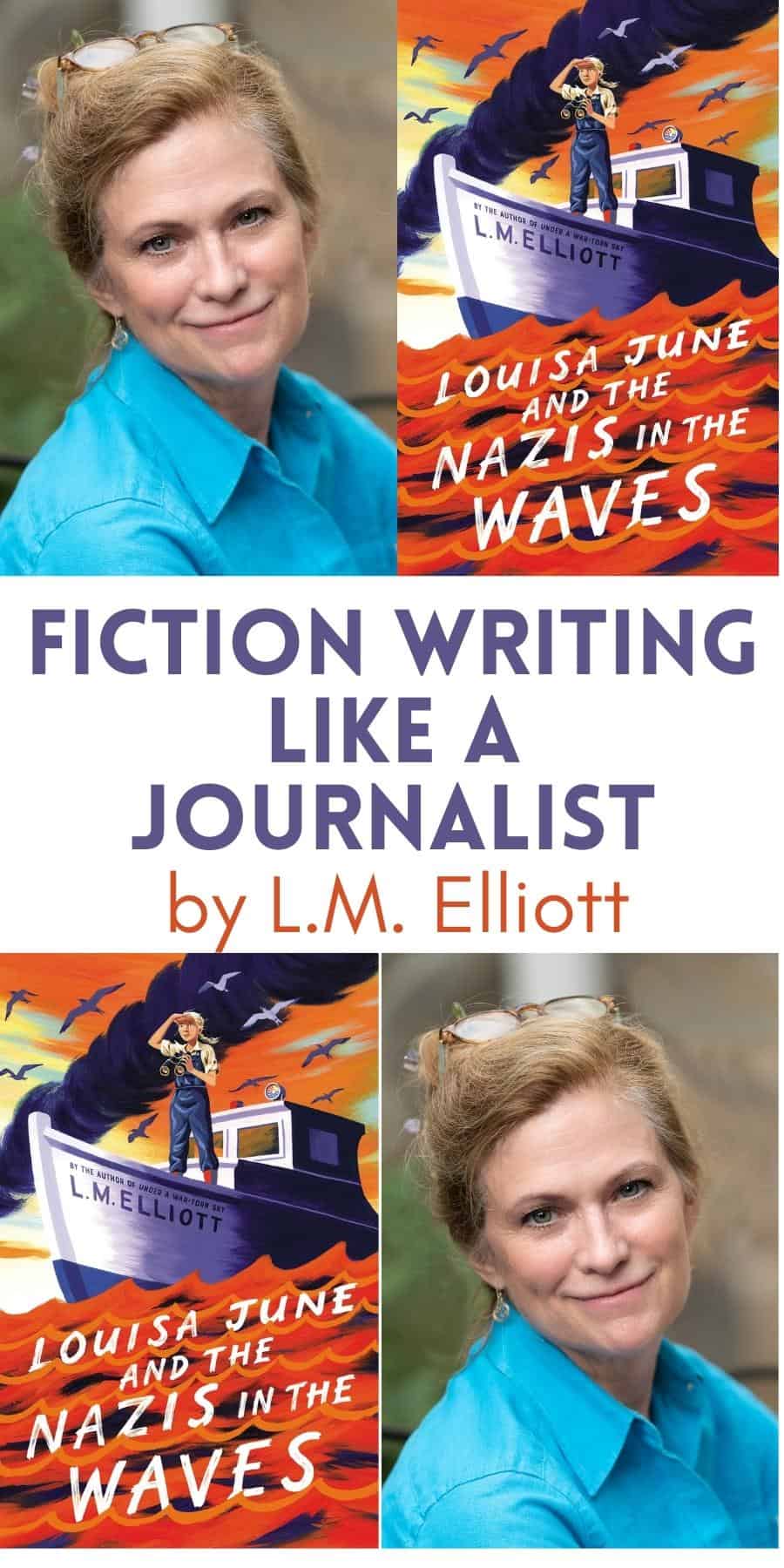

Thinking Like a Journalist (Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves Blog Tour)

This post may contain affiliate links.

Welcome to the Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves Blog Tour!

To celebrate the release of Louisa June and the Nazis on the Waves by L.M. Elliott on March 22nd, 5 sites will be featuring exclusive guest posts from L.M. Elliott plus 5 chances to win a signed copy of Louisa June!

Thinking Like a Journalist

by L.M. Elliott

Twelve novels and twenty years as an author of historical/biographical fiction for young adults and middle graders, I still think of myself as “an accidental novelist.” That’s because I was a magazine reporter for twenty years before that. (Yes, I’m… hmmm… mature!) I became a novelist because of an article I wrote about my father’s homecoming from WWII as “the holiday story” for a December issue of the Washingtonian, where I was a senior writer. A bomber pilot, his plane down, lost behind lines for months, feared to be dead by his parents, my daddy just appeared in the driveway of their family farm—unannounced—five days before Christmas 1944.

I can hear the slight gasp as you read that line.

WWII is full of such heart-rending moments. I received so many letters in response to that article, breathtaking mini-memoirs about other homecomings or final messages from the battlefield. So, when my editor Katherine Tegen asked if I would think about fictionalizing my father’s experiences for teens, I jumped at the chance. I was thrilled to keep the story of those courageous “flyboys” alive for a generation who would not know them personally. Thrilled with the idea of enriching the story with the metaphors, themes, revelations—those “larger truths”—that novels offer. I researched and vastly expanded my protagonist to become an “everyman,” emblematic of the 4,000 American and British boys who survived bailing out of burning planes because of the French and Dutch civilian resistants who helped them.

Honestly, I fully planned to return to my magazine job after writing Under a War-Torn Sky. I thought it would be my one-time fiction. But that novel did so well, I stayed. It’s still my bestselling work. That has far less to do with me than the fact WWII anecdotes are so riveting, so touching, so epic in terms of revealing and pitting the absolute worst, cruel, and terrifying in human beings against the most noble, brave, and kind. All I had to do was “report” the facts, gather those details, to then imagine and write a moving and meaningful story.

I feel the same about Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves. As soon as I read about the sinking of the Menominee tugboat by a Nazi U-boat on March 31, 1944, just off Chincoteague, Virginia, of the 17-year-old teen who perished, the story of Louisa June came to me. Her own voyage to heal and to help her grieving parents, and her own determined quest to find some way to combat Nazis herself. I just listened.

During school visits, I always encourage would-be authors to work for student newspapers, because journalism is such excellent training for fiction-writing. It demands clarity. To stand in other people’s shoes and consider things from their perspective. To come up with a compelling lede—a dramatic opener or a voice that is so evocative from the get-go, a reader can’t resist.

Journalism teaches writers to make deadlines, to write to space thereby learning to choose one stellar adjective over three mediocre. To be quiet and listen, to watch, absorb, then question, then analyze, and then write. The thinnest articles—or novels—come from sitting at a desk, deciding in the hypothetical, what a story should be. Reporting pushes a writer to look for outside wisdom and insights to add to and inform her own, expanding a story from a flat, one-dimensional balloon to a beautiful full orb of color.

I try to always think like a reporter.

As a magazine staffer, I wrote “human interest” stories, tackling large topics by finding a person to humanize them—someone who lived the situation, not just talked about it. I continue that mindset in my historical novels, trying to build characters who experience fears, longings, moments of redefining epiphanies, a person with whom readers empathize, worry about, and turn each page wondering what happens next. (BTW, engaged in a compelling, well-researched story, teens learn history without realizing it!)

Like Henry Forester was in Under a War-Torn Sky, Louisa June is an “everygirl” for ‘tweens and teens on the WWII homefront, suddenly dealing with an unforeseen, deadly menace (for those on the East Coast, right at their doorstep), the anxiety of not knowing what the next day might bring, and the very new and unnervingly grown-up feeling of wanting to join in a “war-effort.”

Journalism teaches writers to look for “revealing details” that show-rather-than tell. Collect enough and you have a powerful, illuminating scene. In Under a War-Torn Sky, for instance, I could tell readers how bitterly cold it was in those bombers—(sometimes 30 below because the plane’s guns were pointed out open bays)—or I could dress my airmen for their mission, first putting on blue long johns wired like electric blankets that they plugged into the circuitry of their plane. I can have Henry, the co-pilot, shout every 20 minutes—in the mayhem of air battles—”Crack down your lines, boys” to remind the crew to squeeze their oxygen masks and lines to break up the spit from their shouting at one another about incoming Messerschmitt’s that froze into thick ice-pellets that could cut off their airflow.

In Louisa June, I could tell readers that Pearl Harbor and Hitler immediately declaring war on us upended everyday life, or I could have her and her mother sitting among buckets and buckets of jonquils they’d grown and cut to take to an annual daffodil festival that had been abruptly canceled because of the panicked scramble to get ready for war. I can say that women were important to the war-effort, picking up blowtorches to weld Liberty Boats, or I can have Louisa June’s spirited big sister argue with her parents about wanting to become a Winnie-Welder, describing her frustration with simply attending dances the USO was hosting to amuse the troops being gathered to deploy.

Well-done, authentic dialogue are potent character-reveals. Word-choice, colloquialisms, or verbal quirks also differentiate individuals within a novel’s ensemble-cast. I learned how to do that writing long articles—six to twelve-thousand-word pieces—that were “fly-on-the-wall” narratives, written in scenes that I would observe by following a subject around for a month or more in addition to interviewing them. (What now is called “creative non-fiction.”) As Pulitzer Prize winning columnist/novelist Anna Quindlen once said about why her fiction’s dialogue carries such punch: “I spent decades writing down people’s words verbatim, how real people talk. I learned that syntax and rhythm were almost as individualistic as a fingerprint. That one quotation, precisely transcribed and intentionally untidied, could delineate a character in a way that exposition never could.”

I also kept an eye on people as I interviewed, making note of mannerisms and the visible emotions of their words. The importance of that really came home in an article I once wrote about a domestic violence case involving a high-ranking government official, an article that grew into an adult nonfiction book. I spent 80+ hours interviewing the victim, notebook in hand to jot down her facial expressions and body language while my tape recorder whirled.

One day she started nudging furniture as we talked. I finally asked what she was doing. She laughed self-consciously and said it was a habit she hadn’t been able to shed, even though she’d been separated from her abusive husband for over a year. He was angered if she vacuumed but didn’t put the furniture legs back into their indentation marks in the carpet. A heartbreaking illustration of the lingering impact of trauma.

I’ve tried to carry that practice on to my novels, describing my characters gestures or hesitation as they talk, moments filled with message for the reader—something narrator Elizabeth Wiley, who has recorded five of my novels including Louisa June, says is so helpful to audiobook performers looking for ways to vocally differentiate characters who may appear all together in a scene. Without clearly delineated voices it’s just a confusing muddle, she says.

As I did for the magazine, I still interview “sources” for my novels. Which I love doing, and which always informs and greatly enriches my narrative choices. Walls, my recent novel about Cold War Berlin, is told through the eyes of an Army teen stationed in the West and his cousin trapped in the Soviet Russia-held East. During preliminary research, I lucked into spotting a website of “Berlin Brats” alumni. The class of 1960-61 were incredibly generous with their time and memories of living in that epicenter of tension between Russia and the United States in the year leading up to the shocking, overnight raising of the Wall.

Just as I did with my magazine pieces, I came to those interviews armed with at least some knowledge of the person, and specific questions. (Never sit down and say, “So tell me about yourself!”) In my reading, I spotted a few references to American personnel and their families being threatened by KGB and Stasi agents who—before the Wall went up—were able to come into West Berlin and troll American officers they hoped to “turn.” Honestly, it sounded too James Bond to be believed. But I asked one of the “brats” about it. He laughed and said matter-of-factly, “Oh yeah, that certainly happened.” Then he mailed me the unpublished memoir of his counter-intelligence officer dad.

What a goldmine! What a game-changer! It was filled with details about the three times the KGB had approached him (on the American post!) and the many spies planted as refugees in the camp that the United States, Britain, and France ran for those who escaped the communist east. The richness critics have kindly found in that novel (NCSS/CBC Notable, a Kirkus Best Historical Fiction) is entirely due to those interviews and the largesse of those “Berlin Brats.” My knowing how to interview people has been vital in terms of my novels’ authenticity and depth of plot, historic details and aura, the historically plausible challenges facing my characters.

A good reporter is always on the lookout for “holes in coverage” or untold stories. So too a novelist. I wrote Walls because I saw there was little written for teens that explained why NATO exists (which seems even more important now given events in Ukraine). If I wanted to “teach” my readers about the Cold War and NATO, nothing is a more dramatic, show-rather-than-tell story humanizing that terrifying nuclear-armed standoff and Russia’s longstanding antipathy and disinformation about Western democracies than the cunningly planned, overnight raising of the Berlin Wall.

I wrote Storm Dog because of pleasure-reading a National Geographic article about the joys of dancing that included a photo of a woman pirouetting with a beautiful gold retriever. The caption called it “canine music freestyle.” I’d NEVER heard of dog-dancing competitions before! As a reporter I would have found a trainer and dog to profile, but in a novel, I could infuse that beautiful symbiosis between dog and person will all sorts of themes and larger questions in a story about a misfit ‘tween finding her definition and redemption through dance and a runaway dog.

I wrote Hamilton and Peggy! because everyone else was focusing on Eliza, and I thought the youngest Schuyler sister, who pops into Miranda’s brilliant musical with only 36 solo words, might provide a fascinating Rosencrantz-and-Guildenstern perspective. Turns out “wicked wit” Peggy was a kick-butt proto-feminist intellectual in her own right—a young, multi-lingual woman (“a favorite at dinner tables and balls”) factually in the right place at the right time to witness many crucial battles and her father’s spy ring in action.

And I initially chose to write Louisa June because when I mentioned the U-boat attacks that terrorized the East Coast in 1942, no one knew anything about it. Nor the fact that the merchant marines crewing those cargo ships and tankers the Nazis targeted suffered the highest casualty rate during WWII of all our armed services. And yet, those salty merchant marine seamen continued to re-up, even old-timers as ancient as 78, like my character Mr. Cooper.

Finally, journalists-turned-novelists tend to keep their creative ego in check. As reporters, we were trained that we were not the story. I see myself, therefore, as a craftswoman rather than “artiste,” which dispels any self-aggrandizing angst! I believe good reporters and authors are purely prisms—capturing and reflecting human pathos, valor, tragic mistakes, and hopes, and in them finding parable.

And that seems a good ending. Another trait hammered in by journalism—knowing when to stop and type: — ### —

Add on Goodreads | Amazon | Bookshop

“Evocatively threaded with the scents and sounds of Tidewater Virginia coastal communities, this story presents a fascinating, lesser-known aspect of the war told from a young girl’s perspective. Successfully tackling the devastation of depression on family relationships, the bitter cost of war, and the uplifting strength of no-nonsense friendship, this story has impressive depth. Superb.”

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Middle grade lovers of World War II historical fiction will find this title engrossing. Elliot’s story delivers facts and a thoughtful approach to characters experiencing grief and depression, while adding some maritime adventure. VERDICT A must-have for all middle grade historical fiction collections. Recommend to those who enjoyed Kimberly Brubaker Bradley’s The War That Saved My Life and Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch’s Making Bombs for Hitler.”

—School Library Journal (starred review)

“Elliott weaves a deeply moving historical tale, including small but significant details that flesh out the situations and characters, even the secondary ones. The extensive and fact-filled backstory in the author’s note gives readers even more context. An excellent middle-grade read that balances adventure, emotions, and family.”

—Booklist (starred review)

“An infrequently explored aspect of WWII history—German submarines torpedoing U.S. cargo ships along America’s East Coast—underpins Elliott’s (Walls) well-crafted novel. Evocative descriptions of the region’s natural life ground this realistic depiction of one family’s efforts to withstand depression and personal tragedy during wartime.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

In this moving and timeless story, award-winning author L. M. Elliott captures life on the U.S. homefront during World War II, weaving a rich portrait of a family reeling from loss and the chilling yet hopeful voyage of fighting for what matters, perfect for fans of The War That Saved My Life.

Days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Hitler declared war on the U.S., unleashing U-boat submarines to attack American ships. Suddenly, the waves outside Louisa June’s farm aren’t for eel-fishing or marveling at wild swans or learning to skull her family’s boat—they’re dangerous, swarming with hidden enemies.

Her oldest brothers’ ships risk coming face-to-face with U-boats. Her sister leaves home to weld Liberty Boat hulls. And then her daddy, a tugboat captain, and her dearest brother, Butler, are caught in the crossfire.

Her mama has always swum in a sea of melancholy, but now she really needs Louisa June to find moments of beauty or inspiration to buoy her. Like sunshine-yellow daffodils, good books, or news accounts of daring rescues of torpedoed passengers.

Determined to help her Mama and aching to combat Nazis herself, Louisa June turns to her quirky friend Emmett and the indomitable Cousin Belle, who has her own war stories—and a herd of cats—to share. In the end, after a perilous sail, Louisa June learns the greatest lifeline is love.

Website | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

L. M. Elliott was a magazine journalist covering women’s issues, mental health, and the performing arts for twenty years before becoming a New York Times best-selling author of historical and biographical fiction. Her twelfth and latest, Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves, is set in Tidewater Virginia during the deadly U-boat attacks on our coast in 1942. Her novels explore a variety of eras (the Italian Renaissance, the American Revolutionary War, WWII, and the Cold War), and are written for a variety of ages. Her works have been named NCSS/CBC Notables, Bank Street College Best Books, Jefferson Cup Honor Books, Kirkus Bests, and Grateful American Book Prize winners. Learn more at www.lmelliott.com and Twitter or Instagram @L_M_Elliott.

KEEP READING

5 Ways to Get Story Ideas by Samantha Clark

This post is a goldmine for writers. I learned so much about writing historical fiction from this talented author. The facts about the Berlin Brats are fascinating.

Thanks for your comment!

This was a fascinating read. I agree with the author that young teens should be exposed to history in a way that speaks to them – and textbooks are not the answer. I am so happy Ms. Elliott has recognized and responded to this need. Thank you, Melissa, for introducing us to these books and to their author. My next stop is Amazon!

I hope you love the book, too!

I had never heard the term “flyboys” before! Also, it is always interesting to learn more about WWII–and about a writer’s process for investigating and creating.

Yes–and I like that this is about a part of history I didn’t know about before, either!

Thank you, Melissa, for introducing me to the novels written by this fascinating person! I of course, will order her latest book to be sent to my grandkids, perhaps as a “basket stuffer” for Easter. As always, I am indebted to you for providing lists of books to keep my two hungry bibliophiles sated!

You’re so welcome, Nancy. Your grandkids are so lucky to have a book-loving grandma!!

(I’m also so excited to read this one — it looks mesmerizing!)