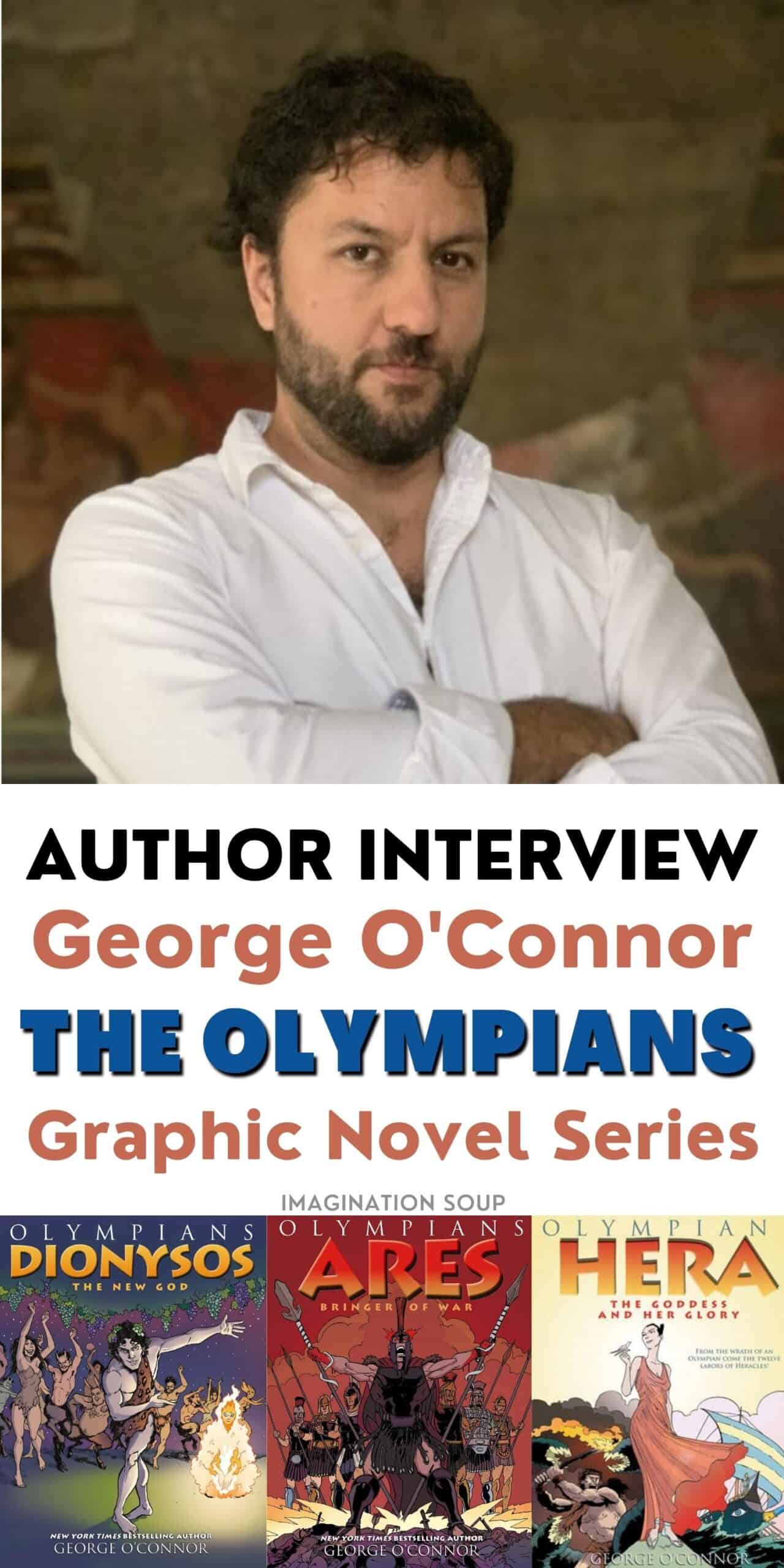

Author Interview: George O’Connor, Creator of The Olympians Series

This post may contain affiliate links.

Both my kids love George O’Conner’s graphic novels because they immerse kids in the traditional Greek myths. George brings them alive with his illustrations and adventurous plotting. If you’re want to read Greek mythology, you’ll want to read The Olympians series by George O’Connor.

In fact, when my 14-years-old aced her Greek mythology English exam, she credited her repeated reading of Rick Riodan and George O’Connor’s books.

We are BIG fans of George O’Connor so I’m thrilled to share a recent interview with him to celebrate the final book in the series, Dionysos.

I’m so grateful for the time he took to thoughtfully consider my questions in this interview.

Author Interview: George O’Connor

Melissa: Why did you choose to write about Greek gods & heroes?

George: When I was a kid one of my biggest “Eureka!” moments in school- a moment when everything made sense to me— was when I was introduced to Greek mythology. I was a child who liked to draw, especially monsters and muscle men, and suddenly in school this was exactly what we were learning about! It was awesome!

However, a lot of the retellings I encountered back then didn’t capture the sheer epic awesomeness of the myths as I read them— they’d be filled with staid drawings based on old Greek pottery, or would become bogged down in an impenetrable text block of poly-syllabic names. Olympians is essentially the series I always wanted to read back then, but didn’t exist yet. So I made it.

Melissa: What is it about the Greek myths that appeal to kids?

George: I have a couple of theories about this. For starters, I think kids like to collect information. This is one of the reasons I believe things like dinosaurs are so popular with generation after generation of kids (and me!). Not only are giant monster-bird-lizards super-cool in an objective sense, but they all have these big long names that mean things (Triceratops= three horn face, for example) and are related to each other in these big families and groupings, and they all have certain roles and niches they fill. It’s a lot of cool stuff, that can be categorized in many different ways— like a collection. Greek mythology, with all its Dionysoses and Hephaistoses and Persephoneses, works the same way.

Additionally, in Greek mythology there is the tantalizing sense of taboo— I know this, in particular, appealed to me. As a child, more than anything, I wanted to be treated as an adult. There was nothing I hated more than when something or someone was talking down to me. Many of the stories in Greek mythology can be considered outlandish, but they also have teeth— they deal with life, death, and all points in between, and they pull no punches. The subject matter of much of Greek mythology would be considered inappropriate for younger audiences— Frog and Toad almost never engaged in cannibalism, for instance— but by virtue of them being the Classics, Greek Mythology is allowed to get pretty gnarly.

Melissa: How do you decide on the narrative arc and specific stories you’ll include in each book?

George: By doing lots and lots of reading. With Olympians, I try not to read other retellings but instead stick to original sources— anything written by an ancient Greek or Roman or someone who believed in these gods. After reading every story I can find, in multiple translations, my head is positively swimming with thoughts on the goddess or god I will be spotlighting. From there, it’s a matter of paring all this info down, boiling it down into a portrait. The corpus of Greek Mythology is so large I couldn’t possibly retell every story, but I can find the few key tales that can define a deity for my readers. Oftentimes, some of the most famous myths— like, say, Orpheus and Eurydice, or Eros and Psyche— don’t make the cut because the story they tell doesn’t adhere enough to my central thesis of painting a personality portrait of a specific Olympian.

Melissa: How long does it take to draw and write an Olympians book from start to finish? Can you explain a bit about that process?

George: It can vary widely, depending on how fast the story gels for me. Comics (or graphic novels if you prefer— I use the term interchangeably) are an amazing art form, far more versatile than any other form of printed media. In comics, you essentially have two pillars upon which to build your story—the words, and the pictures. You can use these pillars to convey two different sets of ideas simultaneously— the words can say one thing, for example, while the images convey a completely different idea, or the two can work together in unison to complement each other. In the best comics, these two pillars combine into a third that is a synthesis of the two working together, conveying info and concepts that words or pictures couldn’t do alone.

This my long way of saying that, for me, in order to get the most storytelling potential out of both the words and the stories in one of my graphic novels I need to work in a strange way. I don’t write a script for my book first, as then I am not using the art to tell the story as much as I can. Conversely, I don’t draw the book first, as there’s no story yet— it’s a real Catch-22. So I do both at the same time— essentially, if it’s an idea better conveyed by words, I write it, and if it’s an idea better conveyed by images, I draw it. After I work out the whole story in a mish-mash of pictures and text I do the hard work of shaping it into panels and pages and page turns and, oh boy, sometimes this whole process can take a loooong time, and that’s not even counting how long it takes to draw finishes!

Basically, with Olympians, the shortest time it took me to complete a book, from the beginning of writing to completion of the finished art was 7 months- the longest was about 14 months.

Melissa: What advice do you have for young cartoonists?

I could easily fill a hundred pages or more with advice here, so I’ll limit myself to this key piece- just do it. So many young artists are so afraid to screw up that they will spend hours upon hours in preparation and never get around to finishing a project, or even starting it. Just do it and know this— you will screw up. A lot. Every page you see in a volume of Olympians, I’ve probably laid it out at least six times, redrawing the compositions over and over until it works. And even then, after all that, no page in Olympians is perfect, because I’m a human and humans are imperfect so that’s kind of the best we can hope for. But what’s cool is, since we’re not perfect, that means we can constantly have room to grow so treat making comics— treat everything you do, really— as an exercise in getting better. Embrace your screw-ups, because every mistake is a chance to learn.

Melissa: What do you tell people who say graphic novels don’t count as reading?

George: Do you mean after I yell “How dare you?!?”

Well, in all seriousness, when someone says this to me (and they do), I explain how graphic novels are reading, just a different sort of reading than they might be familiar with. Refer to my two pillars idea from earlier— a graphic novel is meant to be read multiple times, unlike a standard text. The first time you read a comic, you probably focus mainly on the text. The text’s placement throughout the art, in captions and word bubbles, moves you through the story in a specific way, and at a specific pace. You pick up on the broad strokes of the pictures, but you really won’t notice the full storytelling power of the images until you read it a second time. Then, with a sense of what the text says already in mind, the reader is able to focus more on the pictures and see what they bring to the story, what details they add, what information they convey. They can notice how sometimes the text supports what is happening in the pictures, and how sometimes the pictures reveal that what is being said in the text is not the whole story.

The third, fourth and so-on times a reader reads a graphic novel they will get a more holistic experience, absorbing the story in all its nuances, both verbally and pictorially. It’s this repeat reading of graphic novels that I think upsets some of the “Graphic novels ain’t reading” crowd— I think they observe kids going to the same graphic novels over and over and think that they’re reading comics at the expense of all other types of books. They’re not; it’s just that the meal of a good comic has a lot more to digest.

About Dionysos

Olympians: Dionysos (3/2/22) is a wildly entertaining and accessible story about the god of wine and madness, but also rigorously researched and rooted in a wealth of historical context. O’Connor has devoted much of his life to studying Greek history and myths, and his research for the Olympians series is impeccable. His art does ample justice to the enormity of the subjects at hand. Taking classic superhero art as a jumping-off place, O’Connor’s graceful, dramatic, and highly kinetic illustrations bring these ancient tales to vivid, startling life. And now, more than a decade later, Dionysos completes this exhilarating and beloved graphic novel series.

See ALL of George O’Connor’s Olympian Greek god and hero graphic novels. Boxed set of Zeus, Athena, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Aphrodite here.)

(Note: Be aware that these stick to the actual myths –and the Greek gods weren’t models of purity and morality.)

About George O’Connor

George O’Connor is the New York Times–bestselling author of the Olympians, a series of graphic novels featuring the tragic, dramatic, and epic lives of the Greek gods. George is also the creator of popular picture books such as the New York Times–bestselling Kapow! and I

KEEP READING

I think all kids can relate to what George said about resenting being condescended to and enjoying the gnarly bits of life. I love how he decided to make the book he wished he’d had as a kid—a delightful interview.